News

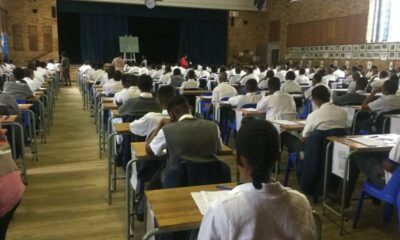

Why Parliament Is Divided Over South Africa’s Matric Pass Mark and Education Standards

Inside the fiery fight over South Africa’s matric pass mark

For a few tense hours in Parliament, education was no longer a policy topic. It became a battle of visions for the country. The long-running argument about South Africa’s so-called thirty percent matric pass mark erupted again, and this time it drew some of the strongest speeches heard in the National Assembly this year.

Although the phrase “thirty percent” has dominated public debate for years, much of the country still misunderstands what it actually means. On Friday, Members of Parliament tried to untangle the myth from the facts but, in doing so, exposed deep frustrations about overcrowded classrooms, children who cannot read for meaning, and a system stretched far beyond its limits.

A call to lift the bar and lift the country

Build One South Africa leader Mmusi Maimane opened the debate with a direct challenge to the Department of Basic Education. South Africa, he argued, must show greater seriousness about academic standards. His concern was not just about percentages. It was about what the numbers say about the future of young South Africans.

He warned that telling a learner they are proficient in a subject with a score of thirty percent does not reflect the skills needed in a world where maths, science, and digital literacy shape job opportunities. Using the previous year’s maths results as an example, he noted that raising the minimum requirement to forty percent would dramatically drop the overall pass rate. At fifty percent, the decline would be even sharper.

To him, this was not a reason to maintain the status quo. It was evidence that the system is pushing pupils through grades without securing the basics. A learner scoring thirty percent is unlikely to qualify for university or even technical training colleges, he cautioned, and employers are unlikely to consider them.

Maimane argued for a phased shift toward a fifty percent benchmark, tied to structural reforms that support learners long before they reach matric.

The warning from the opposition: Lowering standards harms black children

The Economic Freedom Fighters took a blunt approach. MP Mandla Shikwambana did not hold back, saying that a system that accepts thirty percent is effectively burying the futures of Black children. In his view, the problem is not the children. The problem is that they are expected to thrive in schools with overcrowded classrooms, limited resources, and no libraries or laboratories.

He was firm that the pass threshold should be moved to fifty percent. Anything less, he said, is a disservice.

The Minister pushes back: The thirty percent myth must fall

When Basic Education Minister Siviwe Gwarube stepped up, she addressed the heart of the misconception. There is no such thing as an overall thirty percent pass mark, she reminded MPs. Matriculants must satisfy a three-part set of subject requirements. These include at least forty percent in the home language, forty percent in two additional subjects, and thirty percent in three more.

Only a tiny fraction of last year’s candidates managed to pass using the bare minimum combination. Out of more than seven hundred thousand candidates, fewer than two hundred did so. The real problem, she stressed, lives far deeper in the system.

Eight out of ten ten-year-olds cannot read for meaning. That is the crisis that should be keeping policymakers awake at night.

Raising the Grade Twelve bar without improving literacy, teacher support, and early childhood development would only push more pupils out of the system entirely. Improving standards, she said, cannot become the creation of more barriers. It must be matched by improved support.

She pointed to the newly formed National Education and Training Council, which will play a central role in reviewing progression rules and advising on long-term reform.

Beyond pass marks: A more complex South African reality

Another voice in the debate, MP Tebogo Letsie, echoed the need to clear up misinformation. Learners cannot pass matric with thirty percent alone. Different categories of passes, such as bachelor, diploma, and higher certificate, each carry their own requirements, none of which allow an overall thirty percent outcome.

At the same time, he warned that the debate cannot be separated from the country’s broader challenges. Unequal infrastructure, teacher shortages, and resource gaps shape what learners are able to achieve long before they reach their final exams.

The public reaction: Tired of the numbers fight

Parents across the country expressed both anger and exhaustion online. Many want the clear truth rather than viral myths. Others feel that arguing about numbers ignores the deeper reality that children are struggling to read and master early concepts. Social media, as usual, became a space for both frustration and fact-sharing, with many calling for transparency and long-term solutions rather than political point-scoring.

What this means for families right now

The truth is simple. South Africa does not have a single thirty percent pass standard. Learners must meet a layered set of requirements. Yet the worry about quality is legitimate. Until early grade reading improves, until classrooms shrink, and until schools receive the resources they need, tinkering with matric thresholds alone will not change outcomes.

This latest debate may have sounded heated, but it signals something important. Leaders are finally treating early literacy, teacher development, and curriculum reform as urgent national priorities. And parents, who have long been confused by the numbers, might finally get clearer answers.

Follow Joburg ETC on Facebook, Twitter, TikT

For more News in Johannesburg, visit joburgetc.com

Source: The Citizen

Featured Image: MyBroadband