News

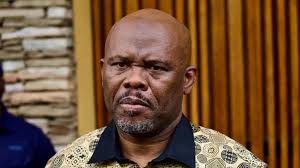

Mchunu Says Political Killings Task Team Should’ve Closed Years Ago, Inside the R435-Million Breakdown

Why Senzo Mchunu Says the Political Killings Task Team Should’ve Been Shut Down Years Ago

Inside the R435-million saga, shifting accountability, and the uncomfortable truth about the PKTT

For years, South Africans have been told that the country’s most dangerous political crimes were being handled by a specialised team, a task force created to chase down the architects of assassinations that have plagued KwaZulu-Natal politics. That team, the Political Killings Task Team (PKTT), became a familiar term in news headlines. What many didn’t know is just how messy, temporary, and expensive that “team” really was.

This week, Police Minister Senzo Mchunu walked into the Madlanga Commission and said the quiet part out loud: the PKTT should have been disbanded long before he made the call. And in saying so, he may have quietly nudged responsibility toward National Police Commissioner Fannie Masemola suggesting that a key decision sat on Masemola’s desk for more than a year.

But this wasn’t just an administrative hiccup. It’s a window into how disorder quietly becomes normalised in South Africa’s security cluster.

A Task Team Built for Six Months… That Ran for Six Years

The PKTT was born from crisis. Back in 2018, political killings in KZN were spiralling councillors murdered, activists disappearing, hitmen roaming freely. President Cyril Ramaphosa ordered an inter-ministerial committee to act, and the PKTT was formed as a “special project”.

Emphasis on project. Not a formal unit. Not a permanent structure. No dedicated budget line.

It was meant to last six months.

Instead, it ran six years and cost taxpayers R435 million.

Inside policing circles, officers joked that “special projects” often live longer than real units. But the PKTT’s survival wasn’t funny, it was costly, clumsy and ultimately unlawful, according to Mchunu’s testimony. After 2022, the task team operated without the legally required extensions, which means the money spent since then may count as irregular expenditure.

It’s the kind of bureaucratic drift that South Africans have come to recognise too well.

The Blame Game Emerges

At the commission, Mchunu, currently on special leave and facing accusations that he shut down the PKTT to derail a criminal investigation, denied everything.

He framed his decision as a matter of good governance:

-

The team’s “operational value” had declined.

-

Its budget ballooned without oversight.

-

And the police service needed those resources back at station level.

But then came the real revelation.

Mchunu said that in December 2023, Commissioner Masemola told him something astonishing: the PKTT had never been a formal police unit, and according to a 2019 work study, it should have been folded into the Murder and Robbery Unit years ago.

Even more damning?

That work study, signed by former commissioner Khehla Sitole was only officially approved by Masemola in June 2025. A full year after officials finalized the new structure.

Mchunu didn’t say Masemola dropped the ball outright, but the implication hung in the room like a thick fog.

If he had signed in March 2024, we wouldn’t be here, the minister suggested.

That’s a remarkably diplomatic way of saying: the delay cost the government time, money, and credibility.

Inside the Commission: A Minister on the Defensive

With Advocate Tembeka Ngcukaitobi at his side, Mchunu painted himself as someone who never interferes in operational policing, “I don’t direct, approve or participate in raids or arrests,” he insisted.

He reminded the inquiry that in decades of politics, he had never once been accused of corruption.

This latest saga, he said, began after KZN Police Commissioner Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi’s 6 July press briefing, a public moment that set off political tremors.

Social media reaction reflected the usual divide:

Some users saw Mchunu as a minister doing the cleanup work others failed to do. Others accused him of scapegoating and political choreography ahead of internal ANC battles.

As one X user asked bluntly:

“How do you run a task team for six years and only realise now it was ‘interim’? Come on.”

South Africans, after all, have long memories of policing scandals, from the collapse of the Hawks’ crime intelligence structure to the disbanding of the Saps inspectorate, which Mchunu himself compared to the PKTT saga.

The Missing Backstory: How the PKTT Grew Out of Control

The 2024 evaluation report, the one Mchunu referenced, painted an uncomfortable picture:

-

Task teams “ran rampant”.

-

Officers were pulled from stations with no plan for the operational gaps left behind.

-

Budgets ballooned without proper accounting.

-

Oversight was practically non-existent.

Deputy National Commissioner Shadrack Sibiya signed off on this report in March 2024, expressing alarm that implementation of the 2019 work study had stalled for years.

To ordinary South Africans, that’s not just a policing headache, it’s a reminder of how state dysfunction quietly spreads. A structure created to fight political assassinations ended up a bureaucratic zombie.

So What Happens to Political Killing Investigations Now?

According to Mchunu, the PKTT’s functions will be absorbed into the Murder and Robbery Unit a move long recommended but only now being actioned.

Critics worry that dissolving the PKTT may bury focus on political killings, especially in KZN where assassinations continue.

Supporters argue that folding investigations back into the SAPS structure is healthier than maintaining an expensive, floating “special project”.

Either way, the spotlight is now fixed on the police’s leadership chain, where signatures were delayed, structures left hanging, and millions spent without continuity.

A Bigger Conversation About Accountability

If there’s one thing this hearing has exposed, it’s not just a lapse it’s a culture of institutional drift.

A task team built for six months became a six-year, multimillion-rand structure.

Senior SAPS leadership failed to implement its own restructuring plan for years.

And the political fallout landed squarely on a minister who insists he simply followed the paper trail.

South Africans deserve clarity, not another chapter in the long, exhausting story of police mismanagement.

As the commission resumes on Thursday, citizens will be watching closely, hoping that for once, accountability stretches beyond blame-shifting and into real reform.

{Source: The Citizen}

Follow Joburg ETC on Facebook, Twitter , TikTok and Instagram

For more News in Johannesburg, visit joburgetc.com