City Updates

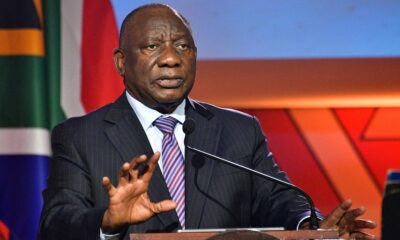

Who must fix South Africa’s abandoned mines as the rehabilitation fight intensifies?

Across many old mining towns in South Africa, the past has a habit of refusing to stay buried. Open shafts, toxic dust, and unstable ground still sit dangerously close to homes, schools, and roads. Now a fresh political clash has reignited a long-running question: who is actually responsible for cleaning up the country’s abandoned mines?

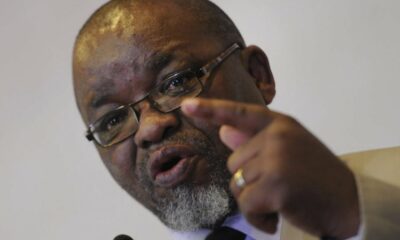

A comment that hit a nerve

The latest tension began after Mineral Resources and Energy Minister Gwede Mantashe told a public inquiry that his department was not legally obliged to rehabilitate old and disused mines. The remark sparked immediate frustration from civil society groups and activists who argue that communities living near these sites continue to face daily danger.

For residents in historic mining regions, this is not an abstract policy debate. Abandoned shafts and sinkholes have already caused injuries and deaths in several areas, keeping the issue emotionally charged and highly visible in public conversations.

A legacy more than a century in the making

South Africa’s mining history stretches back well over a hundred years. That long legacy has left thousands of derelict and ownerless sites scattered across the country. Government records indicate there are thousands of abandoned mines, many of which pose health, safety, and environmental risks for nearby communities.

Officials have acknowledged that these sites can contaminate water, release hazardous dust, and create unstable ground conditions. Because some original mining companies no longer exist, tracing responsibility has become complicated and expensive.

What government says it has done so far

Despite the criticism, the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy has pointed to ongoing rehabilitation work. Recent updates show that at least four asbestos mines in Limpopo and the Northern Cape have been rehabilitated, and about 280 dangerous mine openings have been sealed.

This progress was funded through additional allocations of roughly R180 million in one financial year, followed by more than R134.7 million transferred to Mintek to continue the programme. Officials have also stressed that the number of sites rehabilitated each year depends heavily on the available budget.

Historically, the department has prioritised asbestos mines because of their severe health risks, particularly lung disease linked to exposure.

The funding puzzle and a massive backlog

Experts say the scale of the problem far exceeds current resources. Estimates suggest the rehabilitation backlog could require hundreds of billions of rand to fully address, while existing funding only allows a limited number of sites to be repaired each year.

Mining specialists have also pointed to the existence of industry-funded closure provisions, arguing that these funds were created to ensure environmental rehabilitation when mines shut down. The debate now centres on whether the government should step in when companies fail to meet those obligations.

Activists push back

Community groups and campaigners have been especially vocal. Some activists argue that existing mining laws already place responsibility on the state to enforce rehabilitation and protect residents from harm.

Their frustration is rooted in lived experience. In several mining towns, families still live near open shafts or unstable land left behind decades ago. For them, the issue is less about policy interpretation and more about basic safety.

Why this debate is not going away

The dispute arrives at a time when illegal mining is expanding into both abandoned and active sites, raising security and economic concerns. The government has indicated it wants stronger regulations and more coordinated enforcement while also continuing rehabilitation work where possible.

At its core, the conflict reflects a deeper national dilemma. South Africa’s mineral wealth built entire cities and industries, yet the environmental cost is still being paid by communities long after the mines closed.

Until there is a clear agreement on who must take responsibility and how the cleanup will be funded, abandoned mines will remain more than relics of the past. They will continue to shape the daily reality of the people living closest to them.

Follow Joburg ETC on Facebook, Twitter, TikT

For more News in Johannesburg, visit joburgetc.com

Source: The Citizen

Featured Image: Polity.org.za