Jozi Journeys

From Glamour to Grime: The Unraveling of Hillbrow, Johannesburg’s Lost Icon

If you stand in Hillbrow today, amid the dense, humming energy of its crowded streets, it takes a fierce act of imagination to picture its past. But for those who knew it in the 1960s and 70s, the memory is vivid: a clean, safe, and thrilling cosmopolitan hub. It was Johannesburg’s beating bohemian heart, a forest of apartment towers housing young white professionals, artists, and European immigrants drawn by affordable flats, rooftop parties, and a sense of unshackled modernity. It was, by all accounts from that era, a great place to live.

That version of Hillbrow was a direct creation of apartheid’s brutal engineering. The Group Areas Act and Pass Laws acted as fortified walls, legally preventing Black South Africans from living in the neighbourhood. Its vibrancy was exclusive, its safety artificially enforced by a racist police state.

The Cracks Appear: A Controlled Space Unravels

The first seismic shift began in the mid-1980s. As the apartheid regime crumbled under internal pressure and international condemnation, its spatial controls began to falter. The enforcement of Pass Laws relaxed. Black South Africans, desperate for housing and economic opportunity closer to the city’s core, began moving into Hillbrow’s flats in growing numbers. Change was initially measuredby 1985, the area was roughly 70% white, with a growing Indian, Coloured, and Black minority.

But when the Pass Laws were officially scrapped in 1986, the dam broke. The pace of change was breathtaking. “All-white” blocks transformed into predominantly Black residential buildings within months. This wasn’t a gradual integration; it was a rapid, wholesale demographic inversion driven by decades of pent-up demand. By 1993, estimates suggest about 85% of the inner-city population, including Hillbrow, was Black.

The Tragic Transition: When “Integration” Meant Abandonment

In the 1960s and 1970s, Hillbrow, Johannesburg, South Africa, was known for its cosmopolitan, youthful character, attracting many young white professionals and European migrants because of its affordable flats and vibrant inner-city lifestyle

Hillbrow used to be clean, safe and… pic.twitter.com/1G4U7x55LZ

Rieb van Janbeeck (@RiebvJanbeeck) January 27, 2026

This period is often mislabeled as simply “mixing.” In reality, it was a chaotic and poorly managed transition marked by two catastrophic, simultaneous forces: white flight and state abandonment.

As the old demographic makeup changed, the city council and property ownerslargely white and now fearfulwithdrew investment. Maintenance ceased. Essential services crumbled. Law enforcement, historically focused on controlling Black movement into the area, now seemed to retreat entirely, creating a vacuum. The vibrant, well-kept neighbourhood didn’t gracefully evolve; it was systematically stripped and left to fend for itself.

The new residents inherited a physical shell without the institutional support needed to sustain it. The result was an inevitable descent. Landlords, often absent, turned to exploitative “grey lords.” Overcrowding spiked. The infrastructure, from elevators to plumbing, collapsed. Crime syndicates filled the power vacuum.

Today’s “Hell Hole”: A Legacy of Compound Failures

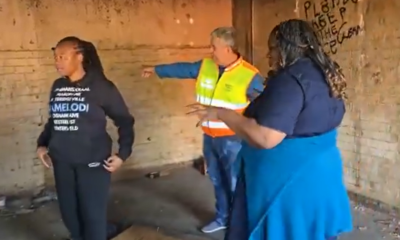

To call today’s Hillbrow a “derelict and dangerous hell hole,” as some do, captures a harsh reality but misses the profound history behind it. Its decay is not a moral failure of its current residents, but the direct consequence of a specific historical sequence: a vibrant but exclusive enclave created by apartheid, followed by a sudden, unplanned inversion without any supportive policy, culminating in decades of municipal neglect.

The story of Hillbrow is South Africa’s urban history in microcosm. It’s a tale of how spaces built on injustice struggle to find a new equilibrium when that injustice is formally removed, but its spatial and economic architecture is left to rot. The gleaming towers of the 1960s still stand, but they are now monuments to a dream that was never meant for everyone, and a warning of what happens when a city stops caring for its own heart.

Follow Joburg ETC on Facebook, Twitter, TikT

For more News in Johannesburg, visit joburgetc.com

Source :X