News

A Town Dying of Thirst: The Human Cost of Kannaland’s Water Collapse

The road is hot enough to burn through plastic sandals. Each morning, as the Karoo sun begins its climb, Sara Frans starts her walk. Seven kilometres there, seven kilometres back, two heavy 5kg bottles in hand. Her feet are sore and swollen, but she has no choice. In Calitzdorp, the tap water is more dirt than drink, and the dam that feeds this town is languishing at 32.8%half what it was this time last year. She is a single mother, and this daily pilgrimage for basic survival is making her “older than I am.”

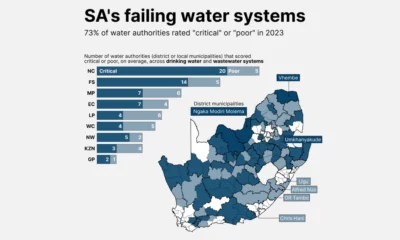

Her agonising trek is the starkest human face of a systemic collapse. The Kannaland municipality, governing Calitzdorp, Ladismith, Zoar, and Van Wyksdorp, is buckling under a trifecta of disaster: a relentless drought, critically ageing infrastructure, and years of alleged financial mismanagement under a controversial leadership. The Western Cape government has flagged these towns as top-risk, but for residents, the warning is too latethe crisis is now.

From Kitchen Taps to Factory Floors: A Regional Paralyzation

The scarcity is crippling every layer of life. In Ladismith, 40km away, the renowned Ladismith Cheese factory is haemorrhaging money. Production manager Darryl Hess says they’ve been forced to slash output and truck in water from farmers with boreholes just to keep operating. Nearby, De Villiers van Zyl’s butchery, Vazco Meat, loses nearly R30,000 a day when the water stops or runs muddy, threatening the livelihoods of his 14 employees.

Farmers stare into an abyss. Kallie Calitz, a 70-year-old wine and olive farmer, began harvesting this week, an act that now feels fraught. “We are very worried,” he says, standing on his Du’SwaRoo farm. He dug a borehole and found nothing. Next season, without rain, looks like “a complete disaster.”

Infrastructure Rot and a Mayor Behind Locked Doors

The crisis is compounded by visible decay. At Ladismith’s Elandsberg Water Seepage Tunnel, a critical point in the supply system, a rusted gate stands open. The roof is riddled with holes. Residents fear it would be easy for someone to poison the town’s water. There is no security.

When questions about this glaring vulnerability were put to Kannaland Mayor Jeffrey Donson, the interaction was telling. The reporter’s phone was seized, and Donson, a figure previously convicted of rape, would only speak from behind a locked door. He acknowledged the infrastructure was “very old” and the security lapse correct, bizarrely warning of a poisonous plant that could kill the town but refusing to name it. He blamed the crisis on a failed dam project he attributed to former president Jacob Zuma and stated, “I am not scared of the president, I am standing with God.”

A Crisis of Leadership and a Long Road Ahead

The DA’s local constituency head, Gillion Bosman, lays responsibility squarely at the mayor’s feet. “There is no plan in place,” he states, accusing the coalition government of squandering provincial support and neglecting infrastructure for years.

Emergency relief is trickling in via organisations like Gift of the Givers, which has deployed tankers and repaired boreholes. But water expert Professor Kevin Winter warns that towns need 25-year plans, not just emergency fixes. “A city or town without water is a catastrophe,” he says.

For now, the burden is carried on the swollen feet of people like Sara Frans. As she points to a distant structure in a field, her only source of clean water, she embodies the failure of a system. The drought is natural. The depth of this crisis is man-made. In the dusty, distressed Karoo, the most basic pact between a government and its peoplethe promise of clean waterhas broken down, one painful step at a time.

{Source: IOL}

Follow Joburg ETC on Facebook, Twitter , TikTok and Instagram

For more News in Johannesburg, visit joburgetc.com