News

Has South Africa Become a Criminal State? Experts Sound the Alarm

South Africa’s crime problem is no longer just about violent robberies, car hijackings, and home invasions. According to political analysts and senior police insiders, the rot has spread deep into the state itself. The warning signs are stark enough that respected voices are now openly calling South Africa a criminal state.

A nation under siege

Professor Andre Duvenhage of North West University has spent years studying the link between weak governance and the rise of organised crime. Speaking on the Nuuspod podcast, he argued that South Africa now fits the profile of a mafia state. His research points to a perfect storm of corruption, a failing justice system, and the deep penetration of criminal syndicates into both politics and business.

KwaZulu-Natal’s provincial police commissioner, Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi, recently echoed these fears. He claimed that criminal networks have infiltrated the very agencies meant to stop them. His allegations include senior police officials obstructing investigations, political leaders interfering with key crime-fighting units, and unqualified individuals being strategically placed in intelligence roles.

According to Mkhwanazi, these moves are not accidental. They are part of a wider scheme to destabilise policing, protect politically connected criminals, and suppress exposure of corruption.

The hallmarks of a mafia state

Duvenhage laid out five global indicators that define a criminal or mafia state. Disturbingly, South Africa ticks every box:

-

A political environment conducive to organised crime.

-

A weakening state that enables criminal enterprises to grow.

-

Infiltration of state institutions by criminal actors.

-

Blurred lines between political and criminal elites.

-

A dysfunctional criminal justice system.

One chilling figure underlines this dysfunction. In South Africa, only one out of every 100 murders results in a successful prosecution.

Organised crime everywhere

From the construction and transport industries to township businesses, mining operations, and even nightlife, organised crime has entrenched itself. Kidnappings for ransom, political killings, and extortion rackets are increasingly common. Criminal syndicates no longer operate in the shadows; they run parts of the economy, sometimes with the help of state officials.

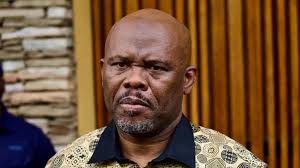

Allegations against Police Minister Senzo Mchunu include claims that he ordered the disbanding of a specialised unit probing political killings. Reports suggest that in early 2025 more than 120 case dockets tied to politically connected individuals were quietly removed. Deputy National Commissioner Shadrack Sibiya has also been accused of obstructing justice by stalling investigations and hoarding files.

South Africa’s global ranking

The Globalised Organised Crime Index paints a sobering picture. South Africa is ranked seventh in the world for criminality, with a score of 7.18. The company it keeps is telling: Colombia, Mexico, Nigeria, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Lebanon. Countries where corruption and criminal networks are deeply embedded in state structures.

For Duvenhage, this is proof that South Africa no longer has the capacity to perform its most basic function as a state: providing security, stability, and order. He warns that crime now threatens not only citizens’ safety but also the constitution and democracy itself.

Public reaction

South Africans have taken to social media in frustration. Some say the mafia-state label finally captures what people live with daily, the sense that criminals act with impunity while government leaders look away. Others argue the label is unfair but admit that the justice system’s collapse is undeniable. The hashtag #CriminalState has trended more than once this year, reflecting public anger at how deeply corruption and violence have taken root.

A sobering reality

For many, the question is no longer whether South Africa has a crime problem, but whether the state itself has been captured by criminality. Analysts like Duvenhage say the evidence is overwhelming. Unless the justice system is rebuilt and political will restored, South Africa risks being governed not by law, but by fear.

Also read: Tshwane’s Demolition Threat Puts Kleinfontein Settlement Back in the Spotlight

Follow Joburg ETC on Facebook, Twitter, TikT

For more News in Johannesburg, visit joburgetc.com

Source: Newsday

Featured Image: iStock