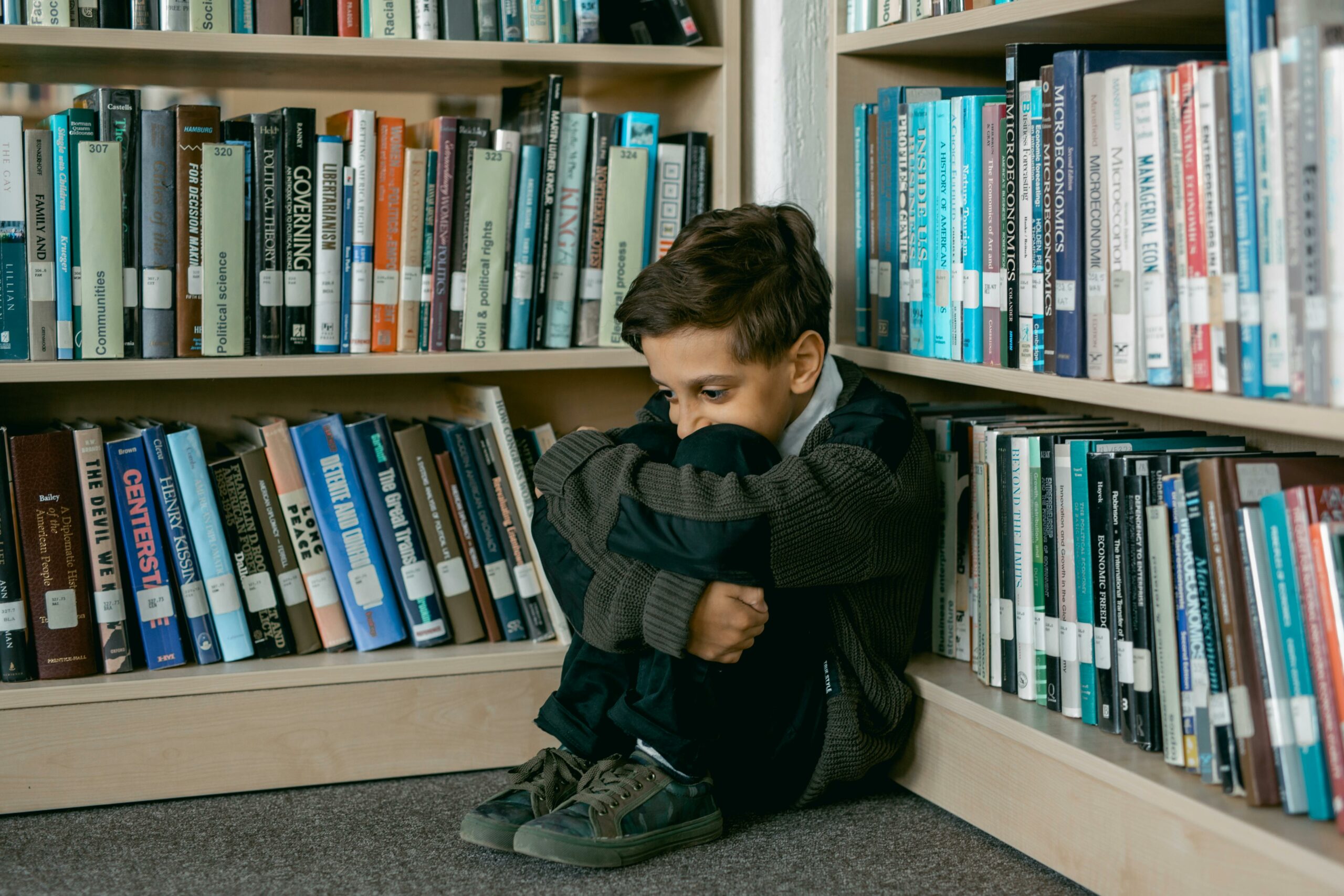

The recent, shocking video from Milnerton High School, where senior pupils allegedly assaulted younger boys with belts and sticks, was more than just an isolated incident. For many parents and educators, it was a terrifying confirmation of a deeper crisis playing out in school corridors and playgrounds across the country. Now, a leading voice in the field is stating plainly what many have feared: South African schools are not doing enough to provide safe havens for learning.

The South African Anti-Bullying Institute (Sabi) has issued a stark warning, accusing schools of a systemic failure in implementing effective safety strategies. According to Sabi director Toto Geza, the promise of a quality education means nothing if a child’s school day is filled with fear.

A Systemic Failure of Safety

“The recent incidents of bullying and violence in schools are a reminder of the urgent need for effective risk management strategies,” Geza stated. “As a nation, we pride ourselves on providing quality education, but are we doing enough to ensure our schools are safe havens for learning? The answer is no.”

The problem, he explains, is not always a complete lack of policy, but a critical failure in execution. “Many schools lack comprehensive safety policies, and those that do have often struggle to implement them effectively. This is unacceptable.”

This gap between policy on paper and protection in practice leaves children vulnerable. Bullying is not a simple rite of passage; it’s a damaging experience that can have lifelong consequences on a child’s mental health and academic performance.

A Blueprint for Change: From Reaction to Prevention

So, what would “doing enough” actually look like? Geza outlines a clear, proactive approach that schools must adopt:

-

Define and Identify: Schools must have a crystal-clear definition of bullying that encompasses its many formsphysical, verbal, and the increasingly pervasive cyberbullying.

-

Assess the Reality: Instead of turning a blind eye, schools need to actively assess the situation. This can be done through anonymous surveys for both pupils and staff and by identifying bullying “hotspots” like bathrooms and hallways.

-

Implement and Intervene: The gathered information is useless if it sits in a filing cabinet. It must be used to launch targeted anti-bullying programmes and interventions.

Geza also pointed to a powerful legal lever that should serve as a “wake-up call” for school administrations. “Section 60 of the South African Schools Act makes it clear: the state is liable for any damage or loss caused by an act or omission in connection with school activities.”

This means that negligence in managing bullying risks isn’t just a moral failingit’s a financial and legal liability for the state and the school.

A Collective Responsibility

The solution, Sabi argues, cannot be the school’s burden alone. It requires a collective effort. “It’s time for us to come together schools, parents, communities, and government to make risk management a priority,” Geza urged.

This means moving beyond punitive measures after an incident occurs and instead fostering a school-wide culture of respect, empathy, and inclusivity from the ground up. It means regular training for teachers on how to spot and intervene in bullying, and programmes for learners that empower bystanders to become “upstanders.”

The message is clear: the wellbeing of our children depends on a fundamental shift from reactive discipline to proactive, ingrained protection. Our schools must become places where children are safe to learn, not just places where they are told to learn.