News

‘If You Don’t Want to Pay More, Use Less’: Parliament Debates New Water Pricing for Farmers

Why SA’s New Water Pricing Plan Has Farmers and MPs Worried

South African farmers are bracing for a major shake-up in the cost of doing business, after government confirmed it would begin phasing out price caps on agricultural water use starting in 2026.

While the Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS) insists the move is economically necessary, MPs and farming communities warn that the changes could drive up food prices and destabilise rural economies already stretched to the limit.

The revised strategy, more than 10 years in the making and officially gazetted in June 2024, marks a historic shift away from apartheid-era subsidies that kept water cheap for (mostly white) commercial agriculture.

What’s changing and why now?

At the centre of the debate is a controversial but crucial clause: the removal of the price cap on irrigation water. For decades, South African irrigators, who use 60% of the country’s water—have paid artificially low rates, originally intended to support white commercial farmers under apartheid.

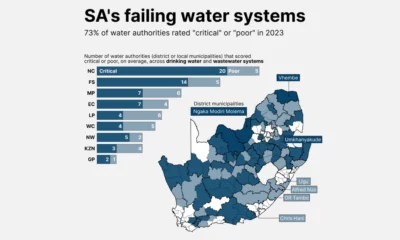

But Director-General Dr Sean Phillips told Parliament on Tuesday that this pricing model is now crippling the country’s ability to maintain dams and water infrastructure. “If we don’t have the money to fix canals and conveyance systems, farmers won’t get water at all,” he warned.

The new plan, approved by National Treasury, is designed to ensure long-term sustainability. It introduces more specific water use categories, allows for targeted pricing models, and aims to be more transparent. A new “non-consumptive” category will even apply to hydropower and solar panel installations on water bodies.

Parliament heats up over food security fears

MK Party MP Visvin Gopal Reddy led the charge against the policy in Parliament, saying the inevitable increase in water costs would trickle down to the average South African consumer.

“If farmers pay more, we all pay more,” he said. “This could cause a surge in food prices, hitting the poor the hardest. What we need is a longer phase-in period and real protection for vulnerable communities.”

Reddy also questioned whether DWS had conducted thorough impact assessments, especially given the current economic climate of high inflation, rising fuel costs and global instability.

Government’s defence: It’s about infrastructure survival

Deputy Minister David Mahlobo defended the policy as a difficult but necessary correction. “Our water infrastructure is in a state of crisis,” he said, adding that South Africa’s water prices have long been out of sync with international benchmarks.

“We can’t keep using outdated apartheid-era policies. Yes, change is painful, but it’s essential,” Mahlobo said. He added pointedly, “If you don’t want to pay more, use less.”

His comment sparked social media buzz, with users accusing government of passing the buck to farmers already battling climate variability, load shedding, and input costs.

“So basically, if you’re poor, just starve,” one user posted on X (formerly Twitter).

“This is going to finish emerging farmers,” another wrote.

Emerging farmers promised waivers, but is it enough?

The department insists that support measures are in place. Emerging and smallholder farmers, for example, will be exempt from paying for raw water. Municipalities will still receive free basic water allocations for indigent households.

But even ANC MPs expressed concern. Keamotseng Stanley Ramaila warned the move could “clash with real-life economic pressures,” including ongoing trade tensions and local inflation.

Phillips promised that professional economists would be hired to evaluate the real-time impact of the cap removals and that the process would be paused if food prices spike.

No money for subsidies, and a municipal debt crisis

One of the thorniest issues? Funding. Treasury has confirmed there’s no money in the fiscus for subsidies.

Phillips questioned whether subsidies are the best approach. “Would it not be more economically rational to price water correctly, rather than distort the system?” he asked.

Compounding the challenge is a ballooning municipal debt crisis. Some water boards, such as Vaal Central, have been forced to operate at a loss. Mangaung Metro has begun paying its current invoices but owes millions in historical debt. Mafikeng’s debt is so chronic that government has now withheld its equitable share funds to force compliance.

Conservation and cautious rollout

The DWS insists that conservation is key to managing future costs.

“Agriculture must be able to grow more food using less water,” said Mahlobo. “That’s the future.”

The department has stressed that any implementation will be gradual and closely monitored, with flexibility to delay rollouts if economic analysis shows harmful effects.

Still, with public trust frayed and farmers already under pressure, the success of the policy may hinge not just on its technical merits, but on whether government can convince South Africans that it’s fair, feasible, and ultimately beneficial.

South Africa’s water pricing reform may make economic sense, but in a country where many go to bed hungry and farmers operate on thin margins, its rollout will need more than spreadsheets, it’ll need heart, timing, and a plan B.

{Source: The Citizen}

Follow Joburg ETC on Facebook, Twitter , TikTok and Instagram

For more News in Johannesburg, visit joburgetc.com